Narra Nickel Mining and Development Corp. v. Redmont Consolidated Mines, G.R. No. 195580, 21 April 2014

♦

Decision, Velasco [J]

♦

Dissenting Opinion, Leonen [J]

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Baguio City

THIRD DIVISION

G.R. No. 195580 April 21, 2014

NARRA NICKEL MINING AND DEVELOPMENT CORP., TESORO MINING AND DEVELOPMENT, INC., and MCARTHUR MINING, INC., Petitioners,

vs.

REDMONT CONSOLIDATED MINES CORP., Respondent.

DISSENTING OPINION

LEONEN, J.:

Investments into our economy are deterred by interpretations of law that are not based on solid ground and sound rationale. Predictability in policy is a very strong factor in determining investor confidence.

The so-called "Grandfather Rule" has no statutory basis. It is the Control Test that governs in determining Filipino equity in corporations. It is this test that is provided in statute and by our most recent jurisprudence.

Furthermore, the Panel of Arbitrators created by the Philippine Mining Act is not a court of law. It cannot decide judicial questions with finality. This includes the determination of whether the capital of a corporation is owned or controlled by Filipino citizens. The Panel of Arbitrators renders arbitral awards. There is no dispute and, therefore, no competence for arbitration, if one of the parties does not have a mining claim but simply wishes to ask for a declaration that a corporation is not qualified to hold a mining agreement. Respondent here did not claim a better right to a mining agreement. By forum shopping through multiple actions, it sought to disqualify petitioners. The decision of the majority rewards such actions.

In this case, the majority's holding glosses over statutory provisions1 and settled jurisprudence.2

Thus, I disagree with the ponencia in relying on the Grandfather Rule. I disagree with the finding that petitioners Narra Nickel Mining and Development Corp. (Narra), Tesoro Mining and Development, Inc. (Tesoro), and McArthur Mining, Inc. (McArthur) are not Filipino corporations. Whether they should be qualified to hold Mineral Production Sharing Agreements (MPSA) should be the subject of proper proceedings in accordance with this opinion. I disagree that the Panel of Arbitrators (POA) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) has jurisdiction to disqualify an applicant for mining activities on the ground that it does not have the requisite Filipino ownership.

Furthermore, respondent Redmont Consolidated Mines Corp. (Redmont) has engaged in blatant forum shopping. The Court of Appeals3 is in error for sustaining the POA. Thus, its findings that Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur are not qualified corporations must be rejected.

To recapitulate, Redmont took interest in undertaking mining activities in the Province of Palawan. Upon inquiry with the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, it discovered that Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur had standing MPSA applications for its interested areas.4

Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur are successors-in-interest of other corporations that have earlier pursued MPSA applications:

1. Narra intended to succeed Alpha Resources and Development Corporation and Patricia Louise Mining and Development Corporation (PLMDC), which held the application MPSA-IV-1-12 covering an area of 3,277 hectares in Barangay Calategas and Barangay San Isidro, Narra, Palawan;5

2. Tesoro intended to succeed Sara Marie Mining, Inc. (SMMI), which held the application MPSA-AMA-IVB-154 covering an area of 3,402 hectares in Barangay Malinao and Barangay Princess Urduja, Narra, Palawan;6

3. McArthur intended to succeed Madridejos Mining Corporation (MMC), which held the application MPSA-AMA-IVB-153 covering an area of more than 1,782 hectares in Barangay Sumbiling, Bataraza, Palawan and EPA-IVB-44 which includes a 3,720-hectare area in Barangay Malatagao, Bataraza, Palawan from SMMI.7

Contending that Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur are corporations whose foreign equity disqualifies them from entering into MPSAs, Redmont filed with the DENR Panel of Arbitrators (POA) for Region IV-B three (3) separate petitions for the denial of the MPSA applications of Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur. In these petitions, Redmont asserted that at least sixty percent (60%) of the capital stock of Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur are owned and controlled by MBMI Resources, Inc. (MBMI), a corporation wholly owned by Canadians.8

Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur countered that the POA did not have jurisdiction to rule on Redmont’s petitions per Section 77 of Republic Act No. 7942, otherwise known as the Philippine Mining Act of 1995 (Mining Act). They also argued that Redmont did not have personality to sue as it had no pending application of its own over the areas in which they had pending applications. They contended that whether they were Filipino corporations has become immaterial as they were already pursuing applications for Financial or Technical Assistance Agreements (FTAA), which, unlike MPSAs, may be entered into by foreign corporations. They added that, in any case, they were qualified to enter into MPSAs as 60% of their capital is owned by Filipinos.9

In a December 14, 2007 resolution,10 the POA held that Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur are foreign corporations disqualified from entering into MPSAs. The dispositive portion of this resolution reads:

WHEREFORE, the Panel of Arbitrators finds the Respondents McArthur Mining Inc., Tesoro Mining and Development, Inc., and Narra Nickel Mining and Development Corp. as, DISQUALIFIED for being considered as Foreign Corporations. Their Mineral Production Sharing Agreement (MPSA) are hereby as [sic], they are DECLARED NULL AND VOID.

Accordingly, the Exploration Permit Applications of Petitioner Redmont Consolidated Mines Corporation shall be GIVEN DUE COURSE, subject to compliance with the provisions of the Mining Law and its implementing rules and regulations.11

Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur then filed appeals before the Mines Adjudication Board (MAB). In a September 10, 2008 order,12 the MAB pointed out that "no MPSA has so far been issued in favor of any of the parties";13 thus, it faulted the POA for still ruling that "[t]heir Mineral Production Sharing Agreement (MPSA) are hereby as [sic], they are DECLARED NULL AND VOID."14

The MAB sustained the contention of Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur that "the Panel does not have jurisdiction over the instant case, and that it should have dismissed the Petition fortwith [sic]."15 It emphasized that:

[W]hether or not an applicant for an MPSA meets the qualifications imposed by law, more particularly the nationality requirement, is a matter that is addressed to the sound discretion of the competent body or agency, in this case the [Securities and Exchange Commission]. In the interest of orderly procedure and administrative efficiency, it is imperative that the DENR, including the Panel, accord full faith and confidence to the contents of Appellants’ Articles of Incorporation, which have undergone thorough evaluation and scrutiny by the SEC. Unless the SEC or the courts promulgate a ruling to the effect that the Appellant corporations are not Filipino corporations, the Board cannot conclude otherwise. This proposition is borne out by the legal presumptions that official duty has been regularly performed, and that the law has been obeyed in the preparation and approval of said documents.16

Redmont then filed with the Court of Appeals a petition for review under Rule 43 of the 1997 Rules on Civil Procedure. This petition was docketed as CA-G.R. SP No. 109703.

In a decision dated October 1, 2010,17 the Court of Appeals, through its Seventh Division, reversed the MAB and sustained the findings of the POA.18

The Court of Appeals noted that the "pivotal issue before the Court is whether or not respondents McArthur, Tesoro and Narra are Philippine nationals under Philippine laws, rules and regulations."19 Noting that doubt existed as to their foreign equity ownerships, the Court of Appeals, Seventh Division, asserted that such equity ownerships must be reckoned via the Grandfather Rule.20 Ultimately, it ruled that Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur "are not Philippine nationals, hence, their MPSA applications should be recommended for rejection by the Secretary of the DENR."21

On the matter of the Panel of Arbitrators’ jurisdiction, the Court of Appeals, Seventh Division, referred to this court’s declarations in Celestial Nickel Mining Exploration Corp. v. Macroasia Corp.22 and considered these pronouncements as "clearly support[ing the conclusion] that the POA has jurisdiction to resolve the Petitions filed by x x x Redmont."23

The motion for reconsideration of Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur was denied by the Court of Appeals through a resolution dated February 15, 2011.24

Hence, this present petition was filed and docketed as G.R. No. 195580.

Apart from these proceedings before the POA, the MAB and the Court of Appeals, Redmont also filed three (3) separate actions before the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Regional Trial Court of Quezon City, and the Office of the President:

First action: On August 14, 2008, Redmont filed a complaint for revocation of the certificates of registration of Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).25 This complaint became the subject of another case (G.R. No. 205513), which was consolidated but later de-consolidated with the present petition, G.R. No. 195580.

In view of this complaint, Redmont filed on September 1, 2008 a manifestation and motion to suspend proceeding[s] before the MAB.26

In a letter-resolution dated September 3, 2009, the SEC’s Compliance and Enforcement Department (CED) ruled in favor of Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur. It applied the Control Test per Section 3 of Republic Act No. 7042, as amended by Republic Act No. 8179, the Foreign Investments Act (FIA), and held that Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur as well as their co-respondents in that case satisfied the requisite Filipino equity ownership.27 Redmont then filed an appeal with the SEC En Banc.

In a decision dated March 25, 2010,28 the SEC En Banc set aside the SEC-CED’s letter-resolution with respect to Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur as the appeal from the MAB’s September 10, 2008 order was then pending with the Court of Appeals, Seventh Division.29 The SEC En Banc considered the assertion that Redmont has been engaging in forum shopping:

It is evident from the foregoing that aside from identity of the parties x xx, the issue(s) raised in the CA Case and the factual foundations thereof x x x are substantially the same as those obtaining the case at bar. Yet, Redmont did not include this CA Case in the Certification Against Forum Shopping attached to the instant Appeal.30

However, with respect to the other respondent-appellees in that case (Sara Marie Mining, Inc., Patricia Louise Mining and Development Corp., Madridejos Mining Corp., Bethlehem Nickel Corp., San Juanico Nickel Corp., and MBMI Resources Inc.), the complaint was remanded to the SEC-CED for further proceedings with the reminder for it to "consider every piece already on record and, if necessary, to conduct further investigation in order to ascertain, consistent with the Grandfather Rule, the true, actual Filipino and foreign participation in each of these five (5) corporations."31

Asserting that the SEC En Banc had already made a definite finding that Redmont has been engaging in forum shopping, Sara Marie Mining, Inc., Patricia Louise Mining and Development Corp., and Madridejos Mining Corp. filed with the Court of Appeals a petition for review under Rule 43 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure. This petition was docketed as CA-G.R. SP No. 113523.

In a decision dated May 23, 2012, the Court of Appeals, Former Tenth Division, found that "there was a deliberate attempt not to disclose the pendency of CA-GR SP No. 109703."32 It concluded that "the partial dismissal of the case before the SEC is unwarranted. It should have been dismissed in its entirety and with prejudice to the complainant."33 The dispositive portion of the decision reads:

WHEREFORE, the Petition is GRANTED. The Decision dated March 25, 2010 of the Securities and Exchange Commission En Banc is REVERSED and SET ASIDE. Accordingly, the complaint for revocation filed by Redmont Consolidated Mines is DISMISSED with prejudice.34 (Emphasis supplied)

On January 22, 2013, the Court of Appeals, Former Tenth Division, issued a resolution35 denying Redmont’s motion for reconsideration.

Aggrieved, Redmont filed the petition for review on certiorari which became the subject of G.R. No. 205513, initially lodged with this court’s First Division. Through a November 27, 2013 resolution, G.R. No. 205513 was consolidated with G.R. No. 195580. Subsequently however, this court’s Third Division de-consolidated the two (2) cases.

Second Action: On September 8, 2008, Redmont filed a complaint for injunction (of the MAB proceedings pending the resolution of the complaint before the SEC) with application for issuance of a temporary restraining order (TRO) and/or writ of preliminary injunction with the Regional Trial Court, Branch 92, Quezon City.36 The Regional Trial Court issued a TRO on September 16, 2008. By then, however, the MAB had already ruled in favor of Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur.37

Third Action: On May 7, 2010, Redmont filed with the Office of the President a petition seeking the cancellation of the financial or technical assistance agreement (FTAA) applications of Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur. In a decision dated April 6, 2011,38 the Office of the President ruled in favor of Redmont. In a resolution dated July 6, 2011,39 the Office of the President denied the motion for reconsideration of Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur. As noted by the ponencia, Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur then filed an appeal with the Court of Appeals. As this appeal has been denied, they filed another appeal with this court, which appeal is pending in another division.40

The petition for review on certiorari subject of G.R. No. 195580 is an appeal from the Court of Appeals’ October 1, 2010 decision in CA-G.R. SP No. 109703 reversing the MAB and sustaining the POA’s findings that Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur are foreign corporations disqualified from entering into MPSAs. The petition also questions the February 15, 2011 resolution of the Court of Appeals denying the motion for reconsideration of Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur.

To reiterate, G.R. No. 195580 was consolidated with another petition – G.R. No. 205513 – through a resolution of this court dated November 27, 2013. G.R. No. 205513 is an appeal from the Court of Appeals, Former Tenth Division’s May 23, 2012 decision and January 22, 2013 resolution in CA-G.R. SP No. 113523. Subsequently however, G.R. No. 195580 and G.R. No. 205513 were de-consolidated.

Apart from G.R. Nos. 195580 and 205513, a third petition has been filed with this court. This third petition is an offshoot of the petitions filed by Redmont with the Office of the President seeking the cancellation of the FTAA applications of Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur.

The main issue in this case relates to the ownership of capital in Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur, i.e., whether they have satisfied the required Filipino equity ownership so as to be qualified to enter into MPSAs.

In addition to this, Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur raise procedural issues: (1) the POA’s jurisdiction over the subject matter of Redmont’s petitions; (2) the supposed mootness of Redmont’s petitions before the POA considering that Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur have pursued applications for FTAAs; and (3) Redmont’s supposed engagement in forum shopping.41

Governing laws

Mining is an environmentally sensitive activity that entails the exploration, development, and utilization of inalienable natural resources. It falls within the broad ambit of Article XII, Section 2 as well as other sections of the 1987 Constitution which refers to ancestral domains42 and the environment.43

More specifically, Republic Act No. 7942 or the Philippine Mining Act, its implementing rules and regulations, other administrative issuances as well as jurisprudence govern the application for mining rights among others. Small-scale mining44 is governed by Republic Act No. 7076, the People’s Small-scale Mining Act of 1991. Apart from these, other statutes such as Republic Act No. 8371, the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act of 1997 (IPRA), and Republic Act No. 7160, the Local Government Code (LGC) contain provisions which delimit the conduct of mining activities.

Republic Act No. 7042, as amended by Republic Act No. 8179, the Foreign Investments Act (FIA) is significant with respect to the participation of foreign investors in nationalized economic activities such as mining. In the 2012 resolution ruling on the motion for reconsideration in Gamboa v. Teves,45 this court stated that "The FIA is the basic law governing foreign investments in the Philippines, irrespective of the nature of business and area of investment."46

Commonwealth Act No. 108, as amended, otherwise known as the Anti-Dummy Law, penalizes those who "allow [their] name or citizenship to be used for the purpose of evading"47 "constitutional or legal provisions requir[ing] Philippine or any other specific citizenship as a requisite for the exercise or enjoyment of a right, franchise or privilege".48

Batas Pambansa Blg. 68, the Corporation Code, is the general law that "provide[s] for the formation, organization, [and] regulation of private corporations."49 The conduct of activities relating to securities, such as shares of stock, is regulated by Republic Act No. 8799, the Securities Regulation Code (SRC).

DENR’s Panel of Arbitrators

has no competence over the

petitions filed by Redmont

The DENR Panel of Arbitrators does not have the competence to rule on the issue of whether the ownership of the capital of the corporations Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur meet the constitutional and statutory requirements. This alone is ample basis for granting the petition.

Section 77 of the Mining Act provides for the matters falling under the exclusive original jurisdiction of the DENR Panel of Arbitrators, as follows:

Section 77. Panel of Arbitrators – x x x Within thirty (30) working days, after the submission of the case by the parties for decision, the panel shall have exclusive and original jurisdiction to hear and decide on the following:

(a) Disputes involving rights to mining areas;

(b) Disputes involving mineral agreements or permit;

(c) Disputes involving surface owners, occupants and claimholders / concessionaires; and

(d) Disputes pending before the Bureau and the Department at the date of the effectivity of this Act.

In 2007, this court’s decision in Celestial Nickel Mining Exploration Corporation v. Macroasia Corp.50 construed the phrase "disputes involving rights to mining areas" as referring "to any adverse claim, protest, or opposition to an application for mineral agreement."51

Proceeding from this court’s statements in Celestial, the ponencia states:

Accordingly, as We enunciated in Celestial, the POA unquestionably has jurisdiction to resolve disputes over MPSA applications subject of Redmont’s petitions. However, said jurisdiction does not include either the approval or rejection of the MPSA applications which is vested only upon the Secretary of the DENR. Thus, the finding of the POA, with respect to the rejection of the petitioners’ MPSA applications being that they are foreign corporation [sic], is valid.52

An earlier decision of this court, Gonzales v. Climax Mining Ltd.,53 ruled on the jurisdiction of the Panel of Arbitrators as follows:

We now come to the meat of the case which revolves mainly around the question of jurisdiction by the Panel of Arbitrators: Does the Panel of Arbitrators have jurisdiction over the complaint for declaration of nullity and/or termination of the subject contracts on the ground of fraud, oppression and violation of the Constitution? This issue may be distilled into the more basic question of whether the Complaint raises a mining dispute or a judicial question.

A judicial question is a question that is proper for determination by the courts, as opposed to a moot question or one properly decided by the executive or legislative branch. A judicial question is raised when the determination of the question involves the exercise of a judicial function; that is, the question involves the determination of what the law is and what the legal rights of the parties are with respect to the matter in controversy.

On the other hand, a mining dispute is a dispute involving (a) rights to mining areas, (b) mineral agreements, FTAAs, or permits, and (c) surface owners, occupants and claimholders/concessionaires. Under Republic Act No. 7942 (otherwise known as the Philippine Mining Act of 1995), the Panel of Arbitrators has exclusive and original jurisdiction to hear and decide these mining disputes. The Court of Appeals, in its questioned decision, correctly stated that the Panel’s jurisdiction is limited only to those mining disputes which raise questions of fact or matters requiring the application of technological knowledge and experience.54 (Emphasis supplied)

Moreover, this court’s decision in Philex Mining Corp. v. Zaldivia,55 which was also referred to in Gonzales, explained what "questions of fact" are appropriate for resolution in a mining dispute:

We see nothing in sections 61 and 73 of the Mining Law that indicates a legislative intent to confer real judicial power upon the Director of Mines. The very terms of section 73 of the Mining Law, as amended by Republic Act No. 4388, in requiring that the adverse claim must "state in full detail the nature, boundaries and extent of the adverse claim" show that the conflicts to be decided by reason of such adverse claim refer primarily to questions of fact. This is made even clearer by the explanatory note to House Bill No. 2522, later to become Republic Act 4388, that "sections 61 and 73 that refer to the overlapping of claims are amended to expedite resolutions of mining conflicts * * *." The controversies to be submitted and resolved by the Director of Mines under the sections refer therfore [sic] only to the overlapping of claims and administrative matters incidental thereto.56 (Emphasis supplied)

The pronouncements in Celestial cited by the ponencia were made to address the assertions of Celestial Nickel and Mining Corporation (Celestial Nickel) and Blue Ridge Mineral Corporation (Blue Ridge) that the Panel of Arbitrators had the power to cancel existing mineral agreements pursuant to Section 77 of the Mining Act.57 Thus:

Clearly, POA’s jurisdiction over "disputes involving rights to mining areas" has nothing to do with the cancellation of existing mineral agreements.58

These pronouncements did not undo or abandon the distinction, clarified in Gonzales, between judicial questions and mining disputes. The former are cognizable by regular courts of justice, while the latter are cognizable by the DENR Panel of Arbitrators.

As has been repeatedly acknowledged by the ponencia,59 the Court of Appeals,60 and the Mines Adjudication Board,61 the present case, and the petitions filed by Redmont before the DENR Panel of Arbitrators boil down to the "pivotal issue x x x [of] whether or not [Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur] are Philippine nationals."

This is a matter that entails a consideration of the law. It is a question that relates to the status of Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur and the legal rights (or inhibitions) accruing to them on account of their status. This does not entail a consideration of the specifications of mining arrangements and operations. Thus, the petitions filed by Redmont before the DENR Panel of Arbitrators relate to judicial questions and not to mining disputes. They relate to matters which are beyond the jurisdiction of the Panel of Arbitrators.

Furthermore nowhere in Section 77 of the Republic Act No. 7942 is there a grant of jurisdiction to the Panel of Arbitrators over the determination of the qualification of applicants. The Philippine Mining Act clearly requires the existence of a "dispute" over a mining area,62 a mining agreement,63 with a surface owner,64 or those pending with the Bureau or the Department65 upon the law’s promulgation. The existence of a "dispute" presupposes that the party bringing the suit has a colorable or putative claim more superior than that of the respondent in the arbitration proceedings. After all, the Panel of Arbitrators is supposed to provide binding arbitration which should result in a binding award either in favor of the petitioner or the respondent. Thus, the Panel of Arbitrators is a qualified quasi-judicial agency. It does not perform all judicial functions in lieu of courts of law.

The petition brought by respondent before the Panel of Arbitrators a quo could not have resulted in any kind of award in its favor. It was asking for a judicial declaration at first instance of the qualification of the petitioners to hold mining agreements in accordance with the law. This clearly was beyond the jurisdiction of the Panel of Arbitrators and eventually also of the Mines Adjudication Board (MAB).

The remedy of Redmont should have been either to cause the cancellation of the registration of any of the petitioners with the Securities and Exchange Commission or to request for a determination of their qualifications with the Secretary of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources. Should either the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) or the Secretary of Environment and Natural Resources rule against its request, Redmont could have gone by certiorari to a Regional Trial Court.

Having brought their petitions to an entity without jurisdiction, the petition in this case should be granted.

Mining as a nationalized

economic activity

The determination of who may engage in mining activities is grounded in the 1987 Constitution and the Mining Act.

Article XII, Section 2 of the 1987 Constitution reads:

Section 2. All lands of the public domain, waters, minerals, coal, petroleum, and other mineral oils, all forces of potential energy, fisheries, forests or timber, wildlife, flora and fauna, and other natural resources are owned by the State. With the exception of agricultural lands, all other natural resources shall not be alienated. The exploration, development, and utilization of natural resources shall be under the full control and supervision of the State. The State may directly undertake such activities, or it may enter into co-production, joint venture, or production-sharing agreements with Filipino citizens, or corporations or associations at least 60 per centum of whose capital is owned by such citizens. Such agreements may be for a period not exceeding twenty-five years, renewable for not more than twenty-five years, and under such terms and conditions as may be provided by law. In cases of water rights for irrigation, water supply, fisheries, or industrial uses other than the development of waterpower, beneficial use may be the measure and limit of the grant.

The State shall protect the nation’s marine wealth in its archipelagic waters, territorial sea, and exclusive economic zone, and reserve its use and enjoyment exclusively to Filipino citizens.

The Congress may, by law, allow small-scale utilization of natural resources by Filipino citizens, as well as cooperative fish farming, with priority to subsistence fishermen and fish workers in rivers, lakes, bays, and lagoons.

The President may enter into agreements with foreign-owned corporations involving either technical or financial assistance for large-scale exploration, development, and utilization of minerals, petroleum, and other mineral oils according to the general terms and conditions provided by law, based on real contributions to the economic growth and general welfare of the country. In such agreements, the State shall promote the development and use of local scientific and technical resources.

The President shall notify the Congress of every contract entered into in accordance with this provision, within thirty days from its execution. (Emphasis supplied)

The requirement for nationalization should always be read in relation to Article II, Section 19 of the Constitution which reads:

Section 19. The State shall develop a self-reliant and independent national economy effectively controlled by Filipinos. (Emphasis supplied)

Congress takes part in giving substantive meaning to the phrases "Filipino x x x corporations or associations at least 60 per centum of whose capital is owned by such citizens"66 as well as the phrase "effectively controlled by Filipinos".67 Like all constitutional text, the meanings of these phrases become more salient in context.

Thus, Section 3 (aq) of the Mining Act defines a "qualified person" as follows:

Section 3. Definition of Terms. - As used in and for purposes of this Act, the following terms, whether in singular or plural, shall mean:

x x x x

(aq) "Qualified person" means any citizen of the Philippines with capacity to contract, or a corporation, partnership, association, or cooperative organized or authorized for the purpose of engaging in mining, with technical and financial capability to undertake mineral resources development and duly registered in accordance with law at least sixty per centum (60%) of the capital of which is owned by citizens of the Philippines: Provided, That a legally organized foreign-owned corporation shall be deemed a qualified person for purposes of granting an exploration permit, financial or technical assistance agreement or mineral processing permit. (Emphasis supplied)

In addition, Section 3 (t) defines a "foreign-owned corporation" as follows:

(t) "Foreign-owned corporation" means any corporation, partnerships, association, or cooperative duly registered in accordance with law in which less than fifty per centum (50%) of the capital is owned by Filipino citizens.

Under the Mining Act, nationality requirements are relevant for the following categories of mining contracts and permits: first, exploration permits (EP); second, mineral agreements (MA); third, financial or technical assistance agreements (FTAA); and fourth, mineral processing permits (MPP).

In Section 20 of the Mining Act, "[a]n exploration permit grants the right to conduct exploration for all minerals in specified areas." Section 3 (q) defines exploration as the "searching or prospecting for mineral resources by geological, geochemical or geophysical surveys, remote sensing, test pitting, trenching, drilling, shaft sinking, tunneling or any other means for the purpose of determining the existence, extent, quantity and quality thereof and the feasibility of mining them for profit." DENR Administrative Order No. 2005-15 characterizes an exploration permit as the "initial mode of entry in mineral exploration."68

In Section 26 of the Mining Act, "[a] mineral agreement shall grant to the contractor the exclusive right to conduct mining operations and to extract all mineral resources found in the contract area."

There are three (3) forms of mineral agreements:

1. Mineral production sharing agreement (MPSA) "where the Government grants to the contractor the exclusive right to conduct mining operations within a contract area and shares in the gross output [with the] contractor x x x provid[ing] the financing, technology, management and personnel necessary for the implementation of [the MPSA]";69

2. Co-production agreement (CA) "wherein the Government shall provide inputs to the mining operations other than the mineral resource";70 and

3. Joint-venture agreement (JVA) "where a joint-venture company is organized by the Government and the contractor with both parties having equity shares. Aside from earnings in equity, the Government shall be entitled to a share in the gross output".71

The second paragraph of Section 26 of the Mining Act allows a contractor "to convert his agreement into any of the modes of mineral agreements or financial or technical assistance agreement x x x."

Section 33 of the Mining Act allows "[a]ny qualified person with technical and financial capability to undertake large-scale exploration, development, and utilization of mineral resources in the Philippines" through a financial or technical assistance agreement.

In addition to Exploration Permits, Mineral Agreements, and FTAAs, the Mining Act allows for the grant of mineral processing permits (MPP) in order to "engage in the processing of minerals."72 Section 3 (y) of the Mining Act defines mineral processing as "milling, beneficiation or upgrading of ores or minerals and rocks or by similar means to convert the same into marketable products."

Applying the definition of a "qualified person" in Section 3 (aq) of the Mining Act, a corporation which intends to enter into a Mining Agreement must have (1) "technical and financial capability to undertake mineral resources development" and (2) "duly registered in accordance with law at least sixty per centum (60%) of the capital of which is owned by citizens of the Philippines".73 Clearly, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, as an administrative body, determines technical and financial capability. The DENR, not the Panel of Arbitrators, is also mandated to determine whether the corporation is (a) duly registered in accordance with law and (b) at least "sixty percent of the capital" is "owned by citizens of the Philippines."

Limitations on foreign participation in certain economic activities are not new. Similar, though not identical, limitations are contained in the 1935 and 1973 Constitutions with respect to the exploration, development, and utilization of natural resources.

Article XII, Section 1 of the 1935 Constitution provides:

Section 1. All agricultural, timber, and mineral lands of the public domain, waters, minerals, coal, petroleum, and other mineral oils, all forces or potential energy, and other natural resources of the Philippines belong to the State, and their disposition, exploitation, development, or utilization shall be limited to citizens of the Philippines, or to corporations or associations at least sixty per centum of the capital of which is owned by such citizens, subject to any existing right, grant, lease, or concession at the time of the inauguration of the Government established under this Constitution. Natural resources, with the exception of public agricultural land, shall not be alienated, and no license, concession, or lease for the exploitation, development, or utilization of any of the natural resources shall be granted for a period exceeding twenty-five years, except as to water rights for irrigation, water supply, fisheries, or industrial uses other than the development of water power, in which cases beneficial use may be the measure and the limit of the grant. (Emphasis supplied)

Likewise, Article XIV, Section 9 of the 1973 Constitution states:

Section 9. The disposition, exploration, development, of exploitation, or utilization of any of the natural resources of the Philippines shall be limited to citizens of the Philippines, or to corporations or association at least sixty per centum of the capital of which is owned by such citizens. The Batasang Pambansa, in the national interest, may allow such citizens, corporations, or associations to enter into service contracts for financial, technical, management, or other forms of assistance with any foreign person or entity for the exploitation, development, exploitation, or utilization of any of the natural resources. Existing valid and binding service contracts for financial, the technical, management, or other forms of assistance are hereby recognized as such. (Emphasis supplied)

The rationale for nationalizing the exploration, development, and utilization of natural resources was explained by this court in Register of Deeds of Rizal v. Ung Siu Si Temple74 as follows:

The purpose of the sixty per centum requirement is obviously to ensure that corporations or associations allowed to acquire agricultural land or to exploit natural resources shall be controlled by Filipinos; and the spirit of the Constitution demands that in the absence of capital stock, the controlling membership should be composed of Filipino citizens.75 (Emphasis supplied)

On point are Dean Vicente Sinco’s words, cited with approval by this court in Republic v. Quasha:76

It should be emphatically stated that the provisions of our Constitution which limit to Filipinos the rights to develop the natural resources and to operate the public utilities of the Philippines is one of the bulwarks of our national integrity. The Filipino people decided to include it in our Constitution in order that it may have the stability and permanency that its importance requires. It is written in our Constitution so that it may neither be the subject of barter nor be impaired in the give and take of politics. With our natural resources, our sources of power and energy, our public lands, and our public utilities, the material basis of the nation's existence, in the hands of aliens over whom the Philippine Government does not have complete control, the Filipinos may soon find themselves deprived of their patrimony and living as it were, in a house that no longer belongs to them.77 (Emphasis supplied)

Article XII, Section 2 of the 1987 Constitution ensures the effectivity of the broad economic policy, spelled out in Article II, Section 19 of the 1987 Constitution, of "a self-reliant and independent national economy effectively controlled by Filipinos" and the collective aspiration articulated in the 1987 Constitution’s Preamble of "conserv[ing] and develop[ing] our patrimony."

In this case, Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur are corporations of which a portion of their equity is owned by corporations and individuals acknowledged to be foreign nationals. Moreover, they have each sought to enter into a Mineral Production Sharing Agreement (MPSA). This arrangement requires that foreigners own, at most, only 40% of the capital.

Notwithstanding that they have moved to obtain FTAAs — which are permitted for wholly owned foreign corporations —Redmont still asserts that Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur are in violation of the nationality requirements of the 1987 Constitution and of the Mining Act.78

Narra, Tesoro, and McArthur argue that the Grandfather Rule should not be applied as there is no legal basis for it. They assert that Section 3 (a) of the Foreign Investments Act (FIA) provides exclusively for the Control Test as the means for reckoning foreign equity in a corporation and, ultimately, the nationality of a corporation engaged in or seeking to engage in an activity with nationality restrictions. They fault the Court of Appeals for relying on DOJ Opinion No. 20, series of 2005, a mere administrative issuance, as opposed to the Foreign Investments Act, a statute, for applying the Grandfather Rule.79

Standards for reckoning

foreign equity participation in

nationalized economic

activities

The broad and long-standing nationalization of certain sectors and industries notwithstanding, an apparent confusion has persisted as to how foreign equity holdings in a corporation engaged in a nationalized economic activity shall be reckoned. As have been proffered by the myriad cast of parties and adjudicative bodies involved in this case, there have been two means: the Control Test and the Grandfather Rule.

Paragraph 7 of the 1967 Rules of the Securities and Exchange Commission, dated February 28, 1967, states:

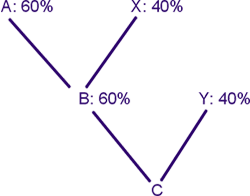

Shares belonging to corporations or partnerships at least 60% of the capital of which is owned by Filipino citizens shall be considered as of Philippine nationality, but if the percentage of Filipino ownership in the corporation or partnership is less than 60%, only the number of shares corresponding to such percentage shall be counted as of Philippine nationality. Thus, if 100,000 shares are registered in the name of a corporation or partnership at least 60% of the capital stock or capital respectively, of which belong to a Filipino citizens, all of the said shares shall be recorded as owned by Filipinos. But if less than 60%, or, say, only 50% of the capital stock or capital of the corporation or partnership, respectively belongs to Filipino citizens, only 50,000 shares shall be counted as owned by Filipinos and the other 50,000 shares shall be recorded as belonging to aliens.80

Department of Justice (DOJ) Opinion No. 20, series of 2005, explains that the 1967 SEC Rules provide for the Control Test and the Grandfather Rule as the means for reckoning foreign and Filipino equity ownership in an "investee" corporation:

The above-quoted SEC Rules provide for the manner of calculating the Filipino interest in a corporation for purposes, among others of determining compliance with nationality requirements (the "Investee Corporation"). Such manner of computation is necessary since the shares of the Investee Corporation may be owned both by individual stockholders ("Investing Individuals") and by corporations and partnerships ("Investing Corporation"). The determination of nationality depending on the ownership of the Investee Corporation and in certain instances, the Investing Corporation.

Under the above-quoted SEC Rules, there are two cases in determining the nationality of the Investee Corporation. The first case is the ‘liberal rule’, later coined by the SEC as the Control Test in its 30 May 1990 Opinion, and pertains to the portion in said Paragraph 7 of the 1967 SEC Rules which states, ‘(s)hares belonging to corporations or partnerships at least 60% of the capital of which is owned by Filipino citizens shall be considered as of Philippine nationality.’ Under the liberal Control Test, there is no need to further trace the ownership of the 60% (or more) Filipino stockholdings of the Investing Corporation since a corporation which is at least 60% Filipino-owned is considered as Filipino.

The second case is the Strict Rule or the Grandfather Rule Proper and pertains to the portion in said Paragraph 7 of the 1967 SEC Rules which states, ‘but if the percentage of Filipino ownership in the corporation or partnership is less than 60%, only the number of shares corresponding to such percentage shall be counted as of Philippine nationality.’ Under the Strict Rule or Grandfather Rule Proper, the combined totals in the Investing Corporation and the Investee Corporation must be traced (i.e., ‘grandfathered’) to determine the total percentage of Filipino ownership.81

DOJ Opinion No. 20, series of 2005, then concluded as follows:

[T]he Grandfather Rule or the second part of the SEC Rule applies only when the 60-40 Filipino-foreign equity ownership is in doubt (i.e., in cases where the joint venture corporation with Filipino and foreign stockholders with less than 60% Filipino stockholdings [or 59%] invests in another joint venture corporation which is either 60-40% Filipino-alien or 59% less Filipino. Stated differently, where the 60-40 Filipino-foreign equity ownership is not in doubt, the Grandfather Rule will not apply.82 (Emphasis supplied)

The conclusion that the Grandfather Rule "applies only when the 60-40 Filipino-foreign equity ownership is in doubt"83 is borne by that opinion’s consideration of an earlier DOJ opinion (i.e., DOJ Opinion No. 18, series of 1989). DOJ Opinion No. 20, series of 2005’s quotation of DOJ Opinion No. 18, series of 1989, reads:

x x x. It is quite clear x x x that the "Grandfather Rule", which was evolved and applied by the SEC in several cases, will not apply in cases where the 60-40 Filipino-alien equity ownership in a particular natural resource corporation is not in doubt.84

A full quotation of the same portion of DOJ Opinion No. 18, series of 1989, reveals that the statement quoted above was made in a very specific context (i.e., a prior DOJ opinion) that necessitated a clarification:

Opinion No. 84, s. 1988 cited in your query is not meant to overrule the aforesaid SEC rule.85 There is nothing in said Opinion that precludes the application of the said SEC rule in appropriate cases. It is quite clear from said SEC rule that the ‘Grandfather Rule’, which was evolved and applied by the SEC in several cases, will not apply in cases where the 60-40 Filipino-alien equity ownership in a particular natural resource corporation is not in doubt.86

DOJ Opinion No. 18, series of 1989, addressed the query made by the Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) "on whether or not it may give due course to the application for incorporation of Far Southeast Gold Resources Inc., (FSEGRI) to engage in mining activities in the Philippines in the light of [DOJ] Opinion No. 84, s. 1988 applying the so-called ‘Grandfather Rule’ x x x."87

DOJ Opinion No. 84, series of 1988, applied the Grandfather Rule. In doing so, it noted that the DOJ has been "informed that in the registration of corporations with the [SEC], compliance with the sixty per centum requirement is being monitored with the ‘Grandfather Rule’"88 and added that the Grandfather Rule is "applied specifically in cases where the corporation has corporate stockholders with alien stockholdings."89

Prior to applying the Grandfather Rule to the specific facts subject of the inquiry it addressed, DOJ Opinion No. 84, series of 1988, first cited the SEC’s application of the Grandfather Rule in a May 30, 1987 opinion rendered by its Chair, Julio A. Sulit, Jr.90

This SEC opinion resolved the nationality of the investee corporation, Silahis International Hotel (Silahis). 31% of Silahis’ capital stock was owned by Filipino stockholders, while 69% was owned by Hotel Properties, Inc. (HPI). HPI, in turn, was 47% Filipino-owned and 53% alien-owned. Per the Grandfather Rule, the 47% indirect Filipino stockholding in Silahis through HPI combined with the 31% direct Filipino stockholding in Silahis translated to an aggregate 63.43% Filipino stockholding in Silahis, in excess of the requisite 60% Filipino stockholding required so as to be able to engage in a partly nationalized business.91

In noting that compliance with the 60% requirement has (thus far) been monitored by SEC through the Grandfather Rule and that the Grandfather Rule has been applied whenever a "corporation has corporate stockholders with alien stockholdings,"92 DOJ Opinion No. 84, series of 1988, gave the impression that the Grandfather Rule is all-encompassing. Hence, the clarification in DOJ Opinion No. 18, series of 1989, that the Grandfather Rule "will not apply in cases where the 60-40 Filipino-alien equity ownership x x x is not in doubt."93 This clarification was affirmed in DOJ Opinion No. 20, series of 2005, albeit rephrased positively as against DOJ Opinion No. 19, series of 1989’s negative syntax (i.e., "not in doubt"). Thus, DOJ Opinion No. 20, series of 2005, declared, that the Grandfather Rule "applies only when the 60-40 Filipino-foreign equity ownership is in doubt."94

Following DOJ Opinion No. 18, series of 1989, the SEC in its May 30, 1990 opinion addressed to Mr. Johnny M. Araneta stated:

[T]the Commission En Banc, on the basis of the Opinion of the Department of Justice No. 18, S. 1989 dated January 19, 1989 voted and decided to do away with the strict application/computation of the so-called "Grandfather Rule" Re: Far Southeast Gold Resources, Inc. (FSEGRI), and instead applied the so-called "Control Test" method of determining corporate nationality.95 (Emphasis supplied)

The SEC’s May 30, 1990 opinion related to the ownership of shares in Jericho Mining Corporation (Jericho) which was then wholly owned by Filipinos. Two (2) corporations wanted to purchase a total of 60% of Jericho’s authorized capital stock: 40% was to be purchased by Gold Field Asia Limited (GFAL), an Australian corporation, while 20% was to be purchased by Gold Field Philippines Corporation (GFPC). GFPC was itself partly foreign-owned. It was 60% Filipino-owned, while 40% of its equity was owned by Circular Quay Holdings, an Australian corporation.96

Applying the Control Test, the SEC’s May 30, 1990 opinion concluded that:

GFPC, which is 60% Filipino owned, is considered a Filipino company. Consequently, its investment in Jericho is considered that of a Filipino. The 60% Filipino equity requirement therefore would still be met by Jericho.

Considering that under the proposed set-up Jericho's capital stock will be owned by 60% Filipino, it is still qualified to hold mining claims or rights or enter into mineral production sharing agreements with the Government.97

Some two years after DOJ Opinion No. 18, series of 2009, Republic Act No. 7042, otherwise known as the Foreign Investments Act (FIA), was enacted. Section 3 (a) of the Foreign Investments Act defines a "Philippine National" as follows:

SEC. 3. Definitions. - As used in this Act:

a) the term "Philippine National" shall mean a citizen of the Philippines or a domestic partnership or association wholly owned by citizens of the Philippines; or a corporation organized under the laws of the Philippines of which at least sixty percent (60%) of the capital stock outstanding and entitled to vote is owned and held by citizens of the Philippines or a corporation organized abroad and registered as doing business in the Philippine under the Corporation Code of which one hundred percent (100%) of the capital stock outstanding and entitled to vote is wholly owned by Filipinos or a trustee of funds for pension or other employee retirement or separation benefits, where the trustee is a Philippine national and at least sixty percent (60%) of the fund will accrue to the benefit of Philippine nationals: Provided, That where a corporation and its non-Filipino stockholders own stocks in a Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) registered enterprise, at least sixty percent (60%) of the capital stock outstanding and entitled to vote of each of both corporations must be owned and held by citizens of the Philippines and at least sixty percent (60%) of the members of the Board of Directors of each of both corporations must be citizens of the Philippines, in order that the corporation shall be considered a Philippine national; (as amended by R.A. 8179). (Emphasis supplied)

Thus, under the Foreign Investments Act, a "Philippine national" is any of the following:

1. a citizen of the Philippines;

2. a domestic partnership or association wholly owned by citizens of the Philippines;

3. a corporation organized under the laws of the Philippines, of which at least 60% of the capital stock outstanding and entitled to vote is owned and held by citizens of the Philippines;

4. a corporation organized abroad and registered as doing business in the Philippines under the Corporation Code, of which 100% of the capital stock outstanding and entitled to vote is wholly owned by Filipinos; or

5. a trustee of funds for pension or other employee retirement or separation benefits, where the trustee is a Philippine national and at least 60% of the fund will accrue to the benefit of Philippine nationals.

The National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) formulated the implementing rules and regulations (IRR) of the Foreign Investments Act. Rule I, Section 1 (b) of these IRR reads:

RULE I

DEFINITIONS

SECTION 1. DEFINITION OF TERMS. — For the purposes of these Rules and Regulations:

x x x x

b. Philippine national shall mean a citizen of the Philippines or a domestic partnership or association wholly owned by the citizens of the Philippines; or a corporation organized under the laws of the Philippines of which at least sixty percent (60%) of the capital stock outstanding and entitled to vote is owned and held by citizens of the Philippines; or a corporation organized abroad and registered as doing business in the Philippines under the Corporation Code of which 100% of the capital stock outstanding and entitled to vote is wholly owned by Filipinos; or a trustee of funds for pension or other employee retirement or separation benefits, where the trustee is a Philippine national and at least sixty percent (60%) of the fund will accrue to the benefits of the Philippine nationals; Provided, that where a corporation and its non-Filipino stockholders own stocks in Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) registered enterprise, at least sixty percent (60%) of the capital stock outstanding and entitled to vote of each of both corporations must be owned and held by citizens of the Philippines and at least sixty percent (60%) of the members of the Board of Directors of each of both corporation must be citizens of the Philippines, in order that the corporation shall be considered a Philippine national. The Control Test shall be applied for this purpose.

Compliance with the required Filipino ownership of a corporation shall be determined on the basis of outstanding capital stock whether fully paid or not, but only such stocks which are generally entitled to vote are considered.

For stocks to be deemed owned and held by Philippine citizens or Philippine nationals, mere legal title is not enough to meet the required Filipino equity. Full beneficial ownership of the stocks, coupled with appropriate voting rights is essential. Thus, stocks, the voting rights of which have been assigned or transferred to aliens cannot be considered held by Philippine citizens or Philippine nationals.

Individuals or juridical entities not meeting the aforementioned qualifications are considered as non-Philippine nationals. (Emphasis supplied)

The Foreign Investments Act’s implementing rules and regulations are clear and unequivocal in declaring that the Control Test shall be applied to determine the nationality of a corporation in which another corporation owns stocks.

From around the time of the issuance of the SEC’s May 30, 1990 opinion addressed to Mr. Johnny M. Araneta where the SEC stated that it "decided to do away with the strict application/computation of the so-called ‘Grandfather Rule’ x x x, and instead appl[y] the so-called ‘Control Test’",98 the SEC "has consistently applied the control test".99 This is a matter expressly acknowledged by Justice Presbitero J. Velasco in his dissent in Gamboa v. Teves:100

It is settled that when the activity or business of a corporation falls within any of the partly nationalized provisions of the Constitution or a special law, the "control test" must also be applied to determine the nationality of a corporation on the basis of the nationality of the stockholders who control its equity.

The control test was laid down by the Department of Justice (DOJ) in its Opinion No. 18 dated January 19, 1989. It determines the nationality of a corporation with alien equity based on the percentage of capital owned by Filipino citizens. It reads:

Shares belonging to corporations or partnerships at least 60% of the capital of which is owned by Filipino citizens shall be considered as Philippine nationality, but if the percentage of Filipino ownership in the corporation or partnership is less than 60% only the number of shares corresponding to such percentage shall be counted as of Philippine nationality.

In a catena of opinions, the SEC, "the government agency tasked with the statutory duty to enforce the nationality requirement prescribed in Section 11, Article XII of the Constitution on the ownership of public utilities," has consistently applied the control test.

The FIA likewise adheres to the control test. This intent is evident in the May 21, 1991 deliberations of the Bicameral Conference Committee (Committees on Economic Affairs of the Senate and House of Representatives), to wit:

CHAIRMAN TEVES. x x x. On definition of terms, Ronnie, would you like anything to say here on the definition of terms of Philippine national?

HON. RONALDO B. ZAMORA. I think we’ve – we have already agreed that we are adopting here the control test. Wasn’t that the result of the –

CHAIRMAN PATERNO. No. I thought that at the last meeting, I have made it clear that the Senate was not able to make a decision for or against the grandfather rule and the control test, because we had gone into caucus and we had voted but later on the agreement was rebutted and so we had to go back to adopting the wording in the present law which is not clearly, by its language, a control test formulation.

HON. ANGARA. Well, I don’t know. Maybe I was absent, Ting, when that happened but my recollection is that we went into caucus, we debated [the] pros and cons of the control versus the grandfather rule and by actual vote the control test bloc won. I don’t know when subsequent rejection took place, but anyway even if the – we are adopting the present language of the law I think by interpretation, administrative interpretation, while there may be some differences at the beginning, the current interpretation of this is the control test. It amounts to the control test.

CHAIRMAN TEVES. That’s what I understood, that we could manifest our decision on the control test formula even if we adopt the wordings here by the Senate version.

x x x x

CHAIRMAN PATERNO. The most we can do is to say that we have explained – is to say that although the House Panel wanted to adopt language which would make clear that the control test is the guiding philosophy in the definition of [a] Philippine national, we explained to them the situation in the Senate and said that we would be – was asked them to adopt the present wording of the law cognizant of the fact that the present administrative interpretation is the control test interpretation. But, you know, we cannot go beyond that.

MR. AZCUNA. May I be clarified as to that portion that was accepted by the Committee. [sic]

MR. VILLEGAS. The portion accepted by the Committee is the deletion of the phrase "voting stock or controlling interest."

This intent is even more apparent in the Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR) of the FIA. In defining a "Philippine national," Section 1(b) of the IRR of the FIA categorically states that for the purposes of determining the nationality of a corporation the control test should be applied.

The cardinal rule in the interpretation of laws is to ascertain and give effect to the intention of the legislator. Therefore, the legislative intent to apply the control test in the determination of nationality must be given effect.101 (Emphasis supplied)

The Foreign Investments Act and its implementing rules notwithstanding, the Department of Justice, in DOJ Opinion No. 20, series of 2005, still posited that the Grandfather Rule is still applicable, albeit "only when the 60-40 Filipino-foreign equity ownership is in doubt."102

Anchoring itself on DOJ Opinion No. 20, series of 2005, the SEC En Banc found the Grandfather Rule applicable in its March 25, 2010 decision in Redmont Consolidated Mines Corp. v. McArthur Mining Corp. (subject of the petition in G.R. No. 205513).103 It asserted that there was "doubt" in the compliance with the requisite 60-40 Filipino-foreign equity ownership:

Such doubt, we believe, exists in the instant case because the foreign investor, MBMI, provided practically all the funds of the remaining appellee-corporations.104

On December 9, 2010, the SEC Office of the General Counsel (OGC) rendered an opinion (SEC-OGC Opinion No. 10-31) effectively abandoning the Control Test in favor of the Grandfather Rule:

We are aware of the Commission's prevailing policy of applying the so-called "Control Test" in determining the extent of foreign equity in a corporation. Since the 1990s, the Commission En Banc, on the basis of DOJ Opinion No. 18, series of 1989 dated January 19, 1989, voted and decided to do away with the strict application/computation of the "Grandfather Rule," and instead applied the "Control Test" method of determining corporate nationality. x x x105

However, we now opine that the Control Test must not be applied in determining if a corporation satisfies the Constitution's citizenship requirements in certain areas of activities. x x x.106

Central to the SEC-OGC’s reasoning is a supposed distinction between Philippine "citizens" and Philippine "nationals". It emphasized that Article XII, Section 2 of the 1987 Constitution used the term "citizen" (i.e., "corporations or associations at least 60 per centum of whose capital is owned by such citizens") and that this terminology was reiterated in Section 3 (aq) of the Mining Act (i.e., "at least sixty per centum (60%) of the capital of which is owned by citizens of the Philippines").107

It added that the enumeration of who the citizens of the Philippines are in Article III, Section 1 of the 1987 Constitution is exclusive and that "only natural persons are susceptible of citizenship".108

Finding support in this court’s ruling in the 1966 case of Palting v. San Jose Petroleum,109 the SEC-OGC asserted that it was necessary to look into the "citizenship of the individual stockholders, i.e., natural persons of [an] investor-corporation in order to determine if the [c]onstitutional and statutory restrictions are complied with."110 Thus, "if there are layers of intervening corporations x x x we must delve into the citizenship of the individual stockholders of each corporation."111 As the SEC-OGC emphasized, "[t]his is the strict application of the Grandfather Rule."112

Between the Grandfather Rule and the Control Test, the SEC-OGC opined that the framers of the 1987 Constitution intended to apply the Grandfather Rule and that the Control Test ran counter to their intentions:

Indeed, the framers of the Constitution intended for the "Grandfather Rule" to apply in case a 60%-40% Filipino-Foreign equity corporation invests in another corporation engaging in an activity where the Constitution restricts foreign participation.113

x x x x

The Control Test creates a legal fiction where if 60% of the shares of an investing corporation are owned by Philippine citizens then all of the shares or 100% of that corporation's shares are considered Filipino owned for purposes of determining the extent of foreign equity in an investee corporation engaging in an activity restricted to Philippine citizens.114

The SEC-OGC reasoned that the invalidity of the Control Test rested on the matter of citizenship:

In other words, Philippine citizenship is being unduly attributed to foreign individuals who own the rest of the shares in a 60% Filipino equity corporation investing in another corporation. Thus, applying the Control Test effectively circumvents the Constitutional mandate that corporations engaging in certain activities must be 60% owned by Filipino citizens. The words of the Constitution clearly provide that we must look at the citizenship of the individual/natural person who ultimately owns and controls the shares of stocks of the corporation engaging in the nationalized/partly-nationalized activity. This is what the framers of the constitution intended. In fact, the Mining Act strictly adheres to the text of the Constitution and does not provide for the application of the Control Test. Indeed, the application of the Control Test has no constitutional or statutory basis. Its application is only by mere administrative fiat.115 (Emphasis supplied)

This court must now put to rest the seeming tension between the Control Test and the Grandfather Rule.

This court’s 1952 ruling in Davis Winship v. Philippine Trust Co.116 cited its 1951 ruling in Filipinas Compania de Seguros v. Christern, Huenefeld and Co., Inc.117 and stated that "the nationality of a private corporation is determined by the character or citizenship of its controlling stockholders."118

Filipinas Compania de Seguros, for its part, specifically used the term "Control Test" (citing a United States Supreme Court decision119) in ruling that the respondent in that case, Christern, Huenefeld and Co., Inc. – the majority of the stockholders of which were German subjects – "became an enemy corporation upon the outbreak of the war."120

Their pronouncements and clear reference to the Control Test notwithstanding, Davis Winship and Filipinas Compania de Seguros do not pertain to nationalized economic activities but rather to corporations deemed to be of a belligerent nationality during a time of war.

In and of itself, this court’s 1966 decision in Palting had nothing to do with the Control Test and the Grandfather Rule. Palting, which was relied upon by SEC-OGC in Opinion No. 10-31, was promulgated in 1966, months before the 1967 SEC Rules and its bifurcated paragraph 7 were adopted.

Likewise, Palting was promulgated before Republic Act No. 5186, the Investments Incentive Act, was adopted in 1967. The Investments Incentive Act was adopted with the declared policy of "accelerat[ing] the sound development of the national economy in consonance with the principles and objectives of economic nationalism,"121 thereby effecting the (1935) Constitution’s nationalization objectives.

It was through the Investments Incentive Act that a definition of a "Philippine national" was established.122 This definition has been practically reiterated in Presidential Decree No. 1789, the Omnibus Investments Code of 1981;123 Executive Order No. 226, the Omnibus Investments Code of 1987;124 and the present Foreign Investments Act.125

This court’s 2009 decision in Unchuan v. Lozada126 referred to Section 3 (a) of the Foreign Investments Act defining "Philippine national". In so doing, this court may be characterized to have applied the Control Test:

In this case, we find nothing to show that the sale between the sisters Lozada and their nephew Antonio violated the public policy prohibiting aliens from owning lands in the Philippines. Even as Dr. Lozada advanced the money for the payment of Antonio’s share, at no point were the lots registered in Dr. Lozada’s name. Nor was it contemplated that the lots be under his control for they are actually to be included as capital of Damasa Corporation. According to their agreement, Antonio and Dr. Lozada are to hold 60% and 40% of the shares in said corporation, respectively. Under Republic Act No. 7042, particularly Section 3, a corporation organized under the laws of the Philippines of which at least 60% of the capital stock outstanding and entitled to vote is owned and held by citizens of the Philippines, is considered a Philippine National. As such, the corporation may acquire disposable lands in the Philippines. Neither did petitioner present proof to belie Antonio’s capacity to pay for the lots subjects of this case.127 (Emphasis supplied)

This court’s 2011 decision in Gamboa v. Teves128 also pertained to the reckoning of foreign equity ownership in a nationalized economic activity (i.e., public utilities). However, it centered on the definition of the term "capital"129 which was deemed as referring "only to shares of stock entitled to vote in the election of directors."130

This court’s 2012 resolution ruling on the motion for reconsideration in Gamboa131 referred to the SEC En Banc’s March 25, 2010 decision in Redmont Consolidated Mines Corp. v. McArthur Mining Corp. (subject of G.R. No. 205513), which applied the Grandfather Rule:

This SEC en banc ruling conforms to our 28 June 2011 Decision that the 60-40 ownership requirement in favor of Filipino citizens in the Constitution to engage in certain economic activities applies not only to voting control of the corporation, but also to the beneficial ownership of the corporation.132

However, a reading of the original 2011 decision will reveal that the matter of beneficial ownership was considered after quoting the implementing rules and regulations of the Foreign Investments Act. The third paragraph of Rule I, Section 1 (b) of these rules states that "[f]ull beneficial ownership of the stocks, coupled with appropriate voting rights is essential." It is this same provision of the implementing rules which, in the first paragraph, declares that "the Control Test shall be applied x x x."

In any case, the 2012 resolution’s reference to the SEC En Banc’s March 25, 2010 decision in Redmont can hardly be considered as authoritative. It is, at most, obiter dictum. In the first place, Redmont was evidently not the subject of Gamboa. It is the subject of G.R. No. 205513, which was consolidated, then de-consolidated, with the present petition. Likewise, the crux of Gamboa was the consideration of the kind/s of shares to which the term "capital" referred, not the applicability of the Control Test and/or the Grandfather Rule. Moreover, the 2012 resolution acknowledges that:

[T]he opinions of the SEC en banc, as well as of the DOJ, interpreting the law are neither conclusive nor controlling and thus, do not bind the Court. It is hornbook doctrine that any interpretation of the law that administrative or quasi-judicial agencies make is only preliminary, never conclusive on the Court. The power to make a final interpretation of the law, in this case the term "capital" in Section 11, Article XII of the 1987 Constitution, lies with this Court, not with any other government entity.133

The Grandfather Rule is not

enshrined in the Constitution

In ruling that the Grandfather Rule must apply, the ponencia relies on the deliberations of the 1986 Constitutional Commission. The ponencia states that these discussions "shed light on how a citizenship of a corporation will be determined."134

The ponencia cites an exchange between Commissioners Bernardo F. Villegas and Jose N. Nolledo:135

MR. NOLLEDO: In Sections 3, 9 and 15, the Committee stated local or Filipino equity and foreign equity; namely, 60-40 in Section 3, 60-40 in Section 9, and 2/3-1/3 in Section 15.

MR. VILLEGAS: That is right.

MR. NOLLEDO: In teaching law, we are always faced with this question: "Where do we base the equity requirement, is it on the authorized capital stock, on the subscribed capital stock, or on the paid-up capital stock of a corporation"? Will the Committee please enlighten me on this?

MR. VILLEGAS: We have just had a long discussion with the members of the team from the UP Law Center who provided us a draft. The phrase that is contained here which we adopted from the UP draft is "60 percent of voting stock."

MR. NOLLEDO: That must be based on the subscribed capital stock, because unless declared delinquent, unpaid capital stock shall be entitled to vote.

MR. VILLEGAS: That is right.

MR. NOLLEDO: Thank you.

With respect to an investment by one corporation in another corporation, say, a corporation with 60-40 percent equity invests in another corporation which is permitted by the Corporation Code, does the Committee adopt the Grandfather Rule?

MR. VILLEGAS: Yes, that is the understanding of the Committee.

MR. NOLLEDO: Therefore, we need additional Filipino capital?

MR. VILLEGAS: Yes.136 (Emphasis supplied)

This court has long settled the interpretative value of the deliberations of the Constitutional Commission. In Civil Liberties Union v. Executive Secretary,137 this court noted:

A foolproof yardstick in constitutional construction is the intention underlying the provision under consideration. Thus, it has been held that the Court in construing a Constitution should bear in mind the object sought to be accomplished by its adoption, and the evils, if any, sought to be prevented or remedied. A doubtful provision will be examined in the light of the history of the times, and the condition and circumstances under which the Constitution was framed. The object is to ascertain the reason which induced the framers of the Constitution to enact the particular provision and the purpose sought to be accomplished thereby, in order to construe the whole as to make the words consonant to that reason and calculated to effect that purpose.138

However, in the same case, this court also said:139

While it is permissible in this jurisdiction to consult the debates and proceedings of the constitutional convention in order to arrive at the reason and purpose of the resulting Constitution, resort thereto may be had only when other guides fail as said proceedings are powerless to vary the terms of the Constitution when the meaning is clear. Debates in the constitutional convention "are of value as showing the views of the individual members, and as indicating the reasons for their votes, but they give us no light as to the views of the large majority who did not talk, much less of the mass of our fellow citizens whose votes at the polls gave that instrument the force of fundamental law. We think it safer to construe the constitution from what appears upon its face." The proper interpretation therefore depends more on how it was understood by the people adopting it than in the framers’s understanding thereof.140 (Emphasis supplied)

As has been stated:

The meaning of constitutional provisions should be determined from a contemporary reading of the text in relation to the other provisions of the entire document. We must assume that the authors intended the words to be read by generations who will have to live with the consequences of the provisions. The authors were not only the members of the Constitutional Commission but all those who participated in its ratification. Definitely, the ideas and opinions exchanged by a few of its commissioners should not be presumed to be the opinions of all of them. The result of the deliberations of the Commission resulted in a specific text, and it is that specific text—and only that text—which we must read and construe.

The preamble establishes that the "sovereign Filipino people" continue to "ordain and promulgate" the Constitution. The principle that "sovereignty resides in the people and all government authority emanates from them" is not hollow. Sovereign authority cannot be undermined by the ideas of a few Constitutional Commissioners participating in a forum in 1986 as against the realities that our people have to face in the present.

There is another, more fundamental, reason why reliance on the discussion of the Constitutional Commissioners should not be accepted as basis for determining the spirit behind constitutional provisions. The Constitutional Commissioners were not infallible. Their statements of fact or status or their inferences from such beliefs may be wrong. x x x.141

It is true that the records of the Constitutional Commission indicate an affirmative reference to the Grandfather Rule. However, the quoted exchange fails to indicate a consensus or the general sentiment of the forty- nine (49) members142 of the Constitutional Commission. What it indicates is, at most, an understanding between Commissioners Nolledo and Villegas, albeit with the latter claiming that the same understanding is shared by the Constitutional Commission’s Committee on National Economy and Patrimony. (Though even then, it is not established if this understanding is shared by the committee members unanimously, or by a majority of them, or is advanced by its leadership under the assumption that it may speak for the Committee.)

The 1987 Constitution is silent on the precise means through which foreign equity in a corporation shall be determined for the purpose of complying with nationalization requirements in each industry. If at all, it militates against the supposed preference for the Grandfather Rule that, its mention in the Constitutional Commission’s deliberations notwithstanding, the 1987 Constitution was, ultimately, inarticulate on adopting a specific test or means.

The 1987 Constitution is categorical in its omission. Its meaning is clear. That is to say, by its silence, it chose to not manifest a preference. Had there been any such preference, the Constitution could very well have said it.

In 1986, when the Constitution was being drafted, the Grandfather Rule and the Control Test were not novel concepts. Both tests have been articulated since as far back as 1967. The Foreign Investments Act, while adopted in 1991, has "predecessor statute[s]"143 dating to before 1986. As earlier mentioned, these predecessors also define the term "Philippine national" and in substantially the same manner that Section 3 (a) of the Foreign Investments Act does.144 It is the same definition: This is the same basis for applying the Control Test.

It is elementary that the Constitution is not primarily a lawyer’s document.145 As the convoluted history of the Control Test and Grandfather Rule shows, even those learned in the law have been in conflict, if not in outright confusion, as to their application. It is not proper to insist upon the Grandfather Rule as enshrined in the Constitution – and as manifesting the sovereign people’s will – when the Constitution makes absolutely no mention of it.

In the final analysis, the records of the Constitutional Commission do not bind this court. As Charles P. Curtis, Jr. said on the role of history in constitutional exegesis:146

The intention of the framers of the Constitution, even assuming we could discover what it was, when it is not adequately expressed in the Constitution, that is to say, what they meant when they did not say it, surely that has no binding force upon us. If we look behind or beyond what they set down in the document, prying into what else they wrote and what they said, anything we may find is only advisory. They may sit in at our councils. There is no reason why we should eavesdrop on theirs.147 (Emphasis provided)

The Control Test is

established by congressional

dictum

The Foreign Investments Act addresses the gap. As this court has acknowledged, "[t]he FIA is the basic law governing foreign investments in the Philippines, irrespective of the nature of business and area of investment."148

The Foreign Investments Act applies to nationalized economic activities under the Constitution. Section 8 of the Foreign Investments Act149 provides that there shall be two (2) component lists, A and B, with List A pertaining to "the areas of activities reserved to Philippine nationals by mandate of the Constitution and specific laws."